Law and the Socratic Dialectician

By John Taylor; 2011 Feb 07, Mulk 01, 167 BE

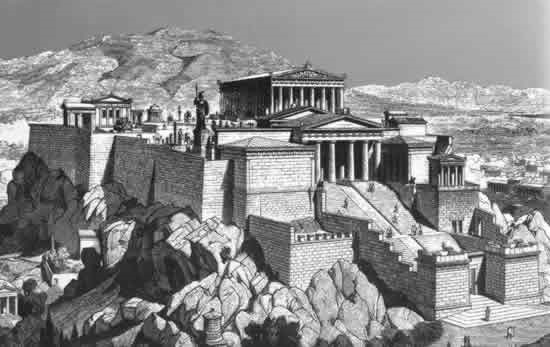

Ancient Athens attracted many geniuses, including the first philosophers, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. They witnessed Lycurgus's attempt in Sparta to establish equality, and Pericles' experimentation in Athens with democracy and liberty. They analyzed why both of these failed to last, and speculated on how they might be improved upon.

In his great work, the Republic, Plato held that at its best kingship, the rule of an individual, would be ideal. A ruling individual does not contradict himself as polyarchies do. Unfortunately, few if any mortals can wield power for long without being corrupted by hubris. Only a true philosopher dare aspire to that. Unfortunately, philosopher kings are rarer than the philosopher's stone. Kings rarely aspire to becoming philosophers, and few philosophers even want to be kings. Similar weaknesses arise from rule of the few, aristocracy, and rule of the people, democracy. Failing the ideal, our best hope is to combine and balance the best features of all three possible types of government, royalism, aristocracy and democracy. Fuse them into a single entity and you get the public thing, the Res Publica or Republic.

In my opinion, though, Plato's greatest masterpiece was his last work, the Laws. We think of sustainability as a modern invention, but Plato held this up as the highest object of all reform. We need to create a polity with the longevity, robustness and stability of Egyptian civilization, which was ancient even in Plato's time. In order to do that, we must strike a measure of justice and right perspective within, and then translate that into good laws.

"If one neglects the rule of due measure, and gives things too great in power to things too small -- sails to ships, food to bodies, offices of rule to souls -- then everything is upset, and they run, through excess of insolence, some to bodily disorders, others to that offspring of insolence, injustice." [Plato, Laws, 691c, <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0166%3Abook%3D3%3Apage%3D691>]

The process of corruption begins, Plato's Athenian Stranger tells us, in pride, which distorts pain and pleasure. We must respond to the two basic human motivations in the right way. If the ruling principle, our reason or wisdom, controls feelings of fear and hope, or better still, directs our fears and hopes towards what we should fear and hope for, then the outcome is good laws.

==========

"Well then we may take it that any human being is one person?"

"Of course."

"But one person has within himself a pair of unwise and conflicting counselors, whose names are pleasure and pain?"

"The fact is as you say."

"He has, besides, anticipations of the future, and these of two sorts. The common name for both sorts is expectation, the special name for anticipation of pain being fear, and for anticipation of its opposite, confidence. And on the top of all, there is judgment, to discern which of these states is better or worse, and when judgment takes the form of a public decision of a city, it has the name of law." (Plato, Laws, 644d, Collected Writings, p. 1244)

==========

Law, then, is the product of many minds undergoing, apart and together, what Socrates, Plato's beloved teacher, had called dialectic. Dialectic is a creative conversation where the learner goes from an idea or thesis, feeling confidence, and that is contradicted and refined by antithesis (fear), and finally the seeker arrives at a consensus, synthesis or reasoned judgment. In the collective sense, the ultimate outcome is law.

We should not concentrate, therefore, on the particular design of a Republic; the most important thing is the legislation that holds it together and gives it life. Make adjustments to the laws, understand the spirit of law, and good leaders and upstanding citizens will arise naturally.

As enough seekers of truth learn to apply dialectic successfully, the polity will hit what we now call a Goldilocks zone, a point of moderation where there is just enough intimate contact among members for equality and freedom to play off on one another. The right amount of equality and inequality comes first. Non-equals naturally want to emulate their betters. Peers want to vie with peers by maintaining a reputation for uprightness and vigour in good works. In order to do this, there must optimum personal freedom so that each can work out his or her own contribution. As Plato puts it in the Laws,

"There is indeed no such boon for a society as this familiar knowledge of citizen by citizen. For where men have no light on each other's characters, but are dark on the subject, no one will ever reach the rank or station that he deserves, or get the justice which is his proper due. Hence in every society it should always be the endeavor of every citizen, before anything else, to prove himself to all his neighbors no counterfeit, but a man of sterling sincerity, and not to be imposed upon by any counterfeiting by others." (Laws, 738e, pp. 1323-1324)

There cannot be so much closeness and unbounded intimacy in a society that outside opinions will dominate personal search. This is imitation, and it intrudes upon the integrity of the individual's dialectic. The tyranny of others' opinions stifles creativity and ultimately kills the polity as well. The way to destroy imitation is through carefully directed conversation, dialectic, which irritates but also leads to a profound realization of what freedom and equality really mean.

Next time I will discuss how Plato's theory might be combined with the Chinese neighborhood helper and Comenius's three magistrates into a new, practical profession called the dialectician.

No comments:

Post a Comment